Some seem to believe that physicians, although human, are part of some master race – one that soldiers on battling their own disease, death and a cadre of other afflictions with head held high and heart hidden beneath their lab coat. Some may even expect that a physician never suffers the daily tolls of life. The patients and families of physicians may have more realistic expectations of their caregiver due in part to the relationship that exists between them. However, too often it is physicians who may have unrealistic assumptions about their own abilities, specifically their own emotional resilience.

For all those times in your professional career that you lost something –a project failed, a job opportunity, an unexpected change in employment, your best work faulted – moving forward on to the next task was usually the path taken. Not missing a beat, not taking a pause – the best that happened was perhaps taking a long deep breath and then the next step, one foot followed by another. In the healthcare field, this dismissal of a situation does not allow time to acknowledge the possible emotional toll taken by an inability to find a diagnosis or medical solution to save a patient.

Jack Tsai, MD, shares, “Instead of an increasing capacity to care for my patients, though, I have noticed that each year of medical training and practice brings more cynicism, burnout and emotional detachment. While so many factors contribute to physician burnout, I suspect a big problem is not taking the time to remember, celebrate and grieve the patients I have lost.”

The physician’s work world is one of efficiency. The goal is to move through each patient encounter effectively, while also developing rapport, establishing the professional physician and patient relationship, and accurately determining the plan of care. Dr. Tsai points out that insurance paperwork, federal requirements and the ongoing need for developing relationships with healthcare insurers creates time away from patients, resulting in a disconnect. One would think such non-patient activities would make losses less impactful and create an emotional distance. Instead it makes the patient encounter focused on gathering data and determining a diagnosis before moving to the next patient. It limits the degree of empathy and compassion that could evolve in a fully present physician and patient experience.

Physicians making time for self-care is one way to avoid becoming a burnout statistic and may also affect patient safety. Self-care following a loss could be attending the patient’s funeral, contributing to a cause well-regarded by the patient, journaling, meditation, talking with trusted colleagues or something as simple as a walk around the block.

Burnout Rates

In 2017, Medscape conducted the Medscape Physician Lifestyle Survey. More than 14,000 physicians representing 30 specialties participated. The findings reflected the following:

- Burnout rates for physicians have been trending upwards with 51 percent of respondents indicating some form of burnout.

- Physician burnout by specialties was reported by 59 percent of Emergency Medicine physicians, 56 percent of OB/GYN and 55 percent of Family Medicine, Internal Medicine and Infectious Disease.

- Severity of burnout, using a scale of 0-4.5, was rate 4.6 by Urology with otolaryngology and oncology at 4.5.

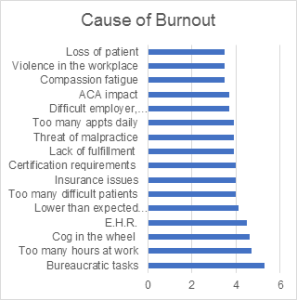

What causes burnout? In the study (using 0-7 scale with 7 being the highest ranked) the following behaviors, tasks, and actions were cited as causal factors:

Resource: Peckham, C. (2017). Medscape Lifestyle Report 2017: Race and Ethnicity. Bias and Burnout. Medscape. Retrieved from https://www.medscape.com/features/slideshow/lifestyle/2017/overview#page=1

Coping

Burnout seems to be a constant threat in the lives of medical professionals. However, burnout does not just result from work and educational stress. Personal life events play heavily in the intensity of burnout experiences.

Side Effects

There are many side effects of burnout. Physicians are groomed early in their careers to put their own emotions aside, directed that expressing those feelings would show weakness and that patients and colleagues would view such emotion as a defect. Compartmentalization happens but at great cost (Harris & Glowinski, 2017). Such setting aside of feelings and emotions causes fatigue, depleted immune systems, sleep disturbances, ruminating, worry, chemical abuse and possibly the loss of compassion and empathy. Short-term coping skills won’t cut it here.

Another side effect is the number of physicians leaving the profession. This is happening at a time when the need for caregivers is increasing. According to Bernard (2017), 49 percent of doctors surveyed in a 2016 Physicians Foundation Report indicated making plans to reduce time spent with patients, early retirement, taking on a nonclinical or administrative role or setting up a concierge practice.

Bad Outcomes

The impact of burnout may culminate in depression and suicidal thoughts. Physician suicide is a public health crisis as one million patients lose their doctors each year. (Symon, 2018). The risk of unchecked depression, stress, alcoholism and chemical dependency lays heavily on the potential for suicide. According to Wibel (2017), after close to a decade of research, some of the following were found in her review of 547 doctor suicides:

- Well-adjusted doctors are also victims of suicide as their outward appearance often does not match their interior self and the dismay and sadness that they feel.

- Doctors have personal problems like everyone else but feel the stress of keeping going, of not letting personal matters come through in their work lives.

- Bullying and sleep deprivation increase suicide risk.

- Doctors and medical students often feel that they cannot obtain confidential medical care.

- Patient deaths in the absence of a lawsuit are still painful and at times unforgivable to the physician.

- Ignoring the emotional health of medical students and residents increases the risk of suicide.

Solutions and Reality

One might assume that exercise, meditation, yoga and communing with nature might be enough to shore up a depleted emotional center. If you Google “stress” and “burnout,” you will find typical, well-regarded solutions, such as stress reduction in the form of exercise, good sleep hygiene and proper diet. While these can be good additions to a daily routine, more is often required to prevent burnout.

Bernard (2017) asserts that physicians must act to take care of themselves emotionally and that may require the assistance of mental health professionals. Psychologists may be able to help guide the physician to a path of improving the relationships in their lives, setting priorities on skills enhancing better patient outcomes, learning strategies to address conflict and dealing with tense situations, identifying options for reducing financial stress and suggesting ways to create work-life balance.

Dr. Wax (2018) stresses that physicians need to learn to put themselves first. Similar advice comes from the airlines. In emergencies, put your own oxygen mask on first. It is difficult to help others when you can barely breathe yourself. Additionally, he points out the importance of having a plan and goals. He recommends taking the time to write down goals, exploring what is desired in five years and then in 10 years for a personal life as well as career. Keep those goals in the forefront each day to ensure the time spent is toward achieving a fulfilling life at work and home.

Resources and References:

Bernard, R. (2017, November 17). 5 ways to improve physician mental health. Medical Economics. Retrieved from: http://medicaleconomics.modernmedicine.com/medical-economics/news/5-ways-improve-physician-mental-health

Dyrbye, L.N., Thomas, M.R., Huntington, J.L., Lawson, K.L., Novotny, P.J., Sloan, J.A.,& Shanafelt, T.D. (2006). Personal life events and medical student burnout: a multicenter study. Academic Medicine 81(4), 374-384.

Harris, D & Glowinski, A. (2017). The deception at the heart of physician burnout #SustainableDocs. Kevin MD. Retrieved from: https://www.kevinmd.com/blog/2017/08/deception-heart-physician-burnout.html

Lagnado, L. (2017). Medical school seeks to make training more compassionate. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved from: https://www.wsj.com/articles/medical-school-seeks-to-make-training-more-compassionate-1490216679

Symon, Robyn. (201). Do No Harm – Exposing the Hippocratic hoax. www.donoharmfilm.com

Tsai, J. (2018). A New Year’s Hope for physicians battling burnout. Medical Economics. Retrieved from: http://medicaleconomics.modernmedicine.com/medical-economics/news/new-years-hope-physicians-battling-burnout?cfcache=true&rememberme=1&elq_mid=310&elq_cid=128647&GUID=644111A8-AB4F-45CA-8AA7-B1EEDD510E4E

Wassersug, J.D. (2018). Physician burnout quote of the week. The Happy MD. Retrieved from: https://www.thehappymd.com/blog/bid/294941/Physician-Burnout-Quote-of-the-Week

Wax, Craig (2018). Physicians must care for themselves to truly help others. Medical Economis. Retrieved from: http://medicaleconomics.modernmedicine.com/medical-economics/news/physicians-must-care-themselves-truly-help-others?cfcache=true&rememberme=1&elq_mid=405&elq_cid=128647&GUID=644111A8-AB4F-45CA-8AA7-B1EEDD510E4E

Wible, P. (2017). What I’ve learned from 547 doctor suicides. Kevin MD. Retrieved from: https://www.kevinmd.com/blog/2017/10/ive-learned-547-doctor-suicides.html

Joan M. Porcaro, RN, BSN, MM, CPHRM, is a senior risk management consultant at the Mutual Insurance Company of Arizona.